Hot Mesh

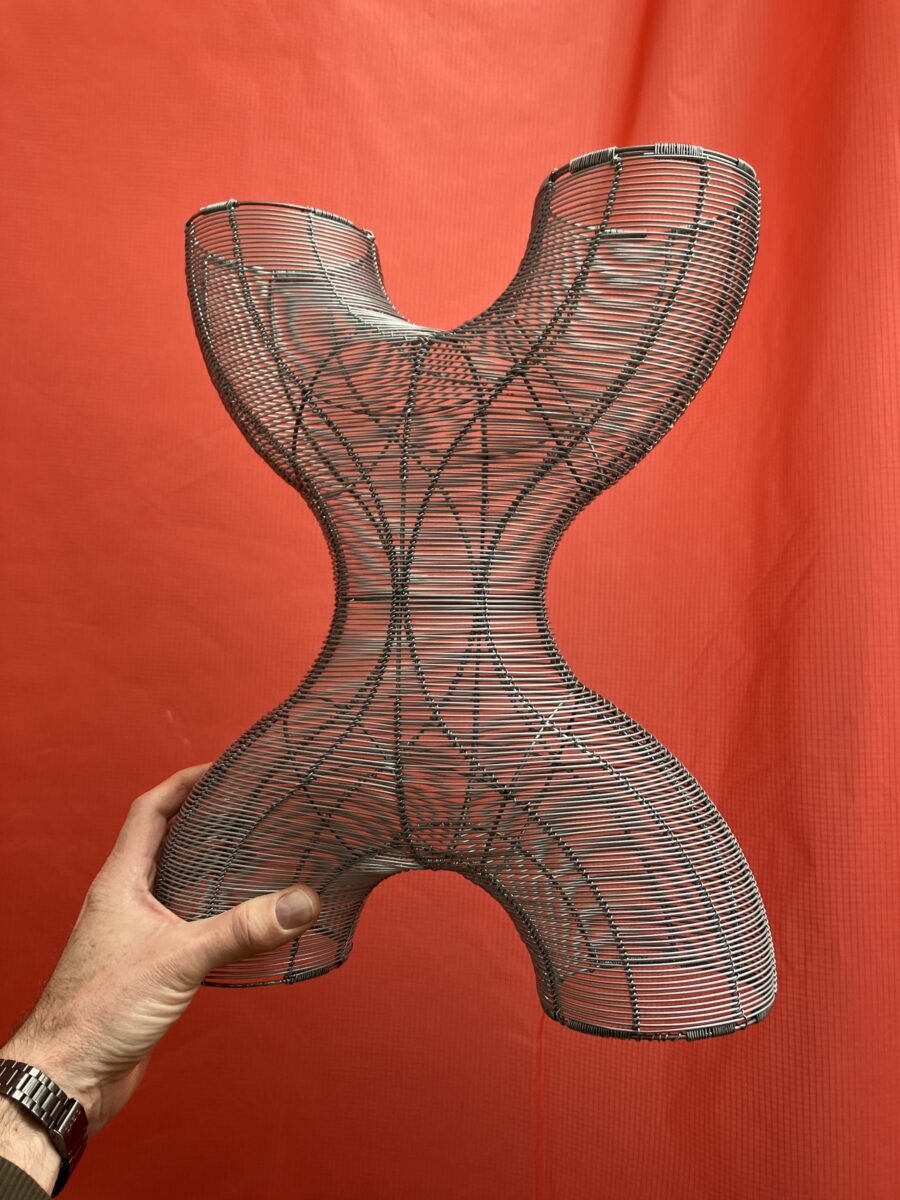

This is Hot Mesh, a modular system for space-making and shade-casting, made of finely woven wire. Its first iteration is MAYA (named for the artist Maya Deren and her surrealist film Meshes of the Afternoon).

Hot Mesh exemplifies the application of skilled handcraft to humble materials to create valuable objects, typical of a vernacular street craft such as Southern African wire art – where time may be available but not much money for materials.

There are 100 days of work (performed by 8 artists over 2 weeks) condensed into this high-value waist-high object made of hardware-store steel fencing wire and finished with industrial zinc electroplating in yellow and clear. Thanks to Spier Arts Trust for their generous support for wire artists’ work on the project.

See a brief video showing the work below (for more, check out our Hot Mesh playlist on the African Robots YouTube channel) and download a brochure above which shows its processes and influences.

What is it?

Hot Mesh is a modular system made up of identical X-shaped modules that stack and interlock to form a wall. Each module is made of thin steel wire finely woven in a basketry-type technique around a thicker wire frame. It is intended as a way of creating spaces and casting complex shadows, lending itself to architecture-art-craft-design. It’s expensive to make (with 90% of the cost being in skilled handcraft).

Each X-module is the width of an LP record cover (around 12 inches or 32cm) and around 38cm (15 inches) tall. To make a wall a little over a metre-square takes about 18 modules; a 2m x 2m wall close to 100. The wire modules are held together with clips 3D-printed in recycled plastic (PETG, the same type used in plastic water bottles) in a skeuomorphic form reminiscent of wire binding.

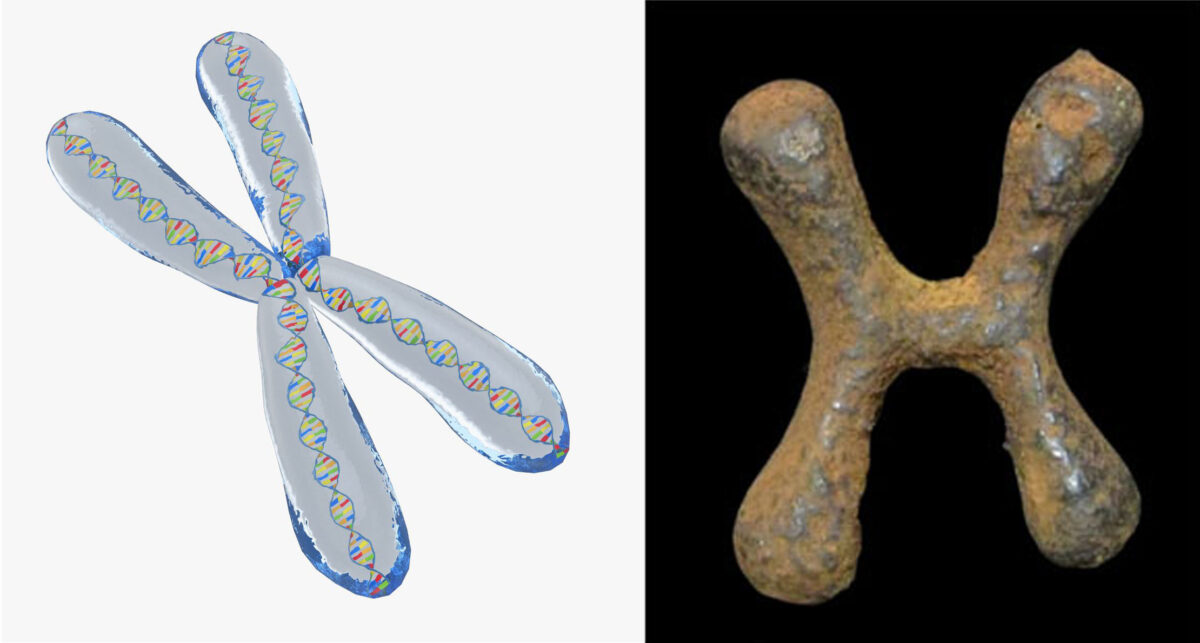

The individual module is a curved and sensuous form reminiscent of the human body. It prompts associations with iconic local forms such as Tonga stools, or wooden headrests made across the continent. They’re similar to precolonial metal ingots, and they have a sciencey side: individually they’re reminiscent of chromosomes, and collectively they stack like molecular structures. Our friend Tapiwa of Tapi-Tapi Icecream (a molecular biologist) said “the bigger piece is essentially a crystal formed from the smaller piece in repeat, right?”. Yep, exactly!

The interlocking form of the overall structures it creates are influenced by contemporary urban patterns seen in African cities, such as Mozambiquan burglar bars and hand-cast breeze blocks, and more ancient repeat patterns such as the stonework of Great Zimbabwe, or those in woven baskets and fabrics. As in our wider work at African Robots, we’re interested in an African ethnomathematics such as that identified in the work of Paulus Gerdes or Ron Eglash.

The wire basketry form (wire artists call this technique ‘plastering’) is influenced by the shark sculptures made by wire artists in Cape Town, which use a similar plastering technique (we’ve used it in our past projects such as Dubship I – Black Starliner and Shapeshifting Chandelier). It’s an example of how at African Robots we design new applications for existing approaches in street wire art.

Who made it?

It was made by a team of eight experienced wire artists, working with African Robots director Ralph Borland. The design is deliberately labour intensive, intended to create an object with high value that generates employment for skilled street-level artisans – many of them economic immigrants and asylum seekers from neighbouring countries in Southern Africa. Most wire artists starting making wire art as children, making the iconic ‘wire car’ for themselves and their friends. Here’s a description that opens a paper in Journal of Futures Studies about our work:

A common sight in Southern African cities is that of ‘wire artists’ plying their trade in public places. These are men who make by hand and sell largely ornamental objects in galvanised steel wire, a common hardware product. The wire-frames they make are often combined with coloured-glass beads, and depict subjects such as animals, fish, birds, flowers, cars, bicycles, and aeroplanes. These products are offered for sale to passersby – frequently to motorists at busy traffic intersections. Making and selling wire art is a means of income for these men, in a country with very low levels of formal employment.

SPACECRAFT: A Southern Interventionist Art Project by Ralph Borland, in Journal of Futures Studies, June 2019

“I arrived at the form by cutting into an interconnected 3D pattern of interlocking chains that I’d dreamed up, sketched and modelled”, says Ralph. He worked in plasticine for the initial maquette, and made engineering drawings and a simple 3D model for digital fabrication. Long time African Robots collaborator Farai Kenyemba made the first wire art sample, working on it between sales at his roadside pitch.

Our friends at Amnova, who are developing locally-appropriate and environmentally-friendly ways of printing objects in a range of materials, did 3D visualisation and fabrication of a printed maquette (and later the 3D-printed clips that hold the modules together). Denis, Nick and Alex and the rest of the team are passionate about empowering Africa as a global leader in sustainable manufacturing and advanced technology development. Fabrication jigs were laser cut by long time collaborators Boyd and Ogier. We shot the finished work in the courtyard of Woodstock Cycle Works – thanks Nic and Nils!

How was it made?

Hot Mesh uses some of the essential techniques of street wire art, including making as much of the main wire frame as possible with a single piece of unbroken wire. We used jigs laser cut from wood to guide the work. Jigs were made of the complete module, in both male and female forms to check for uniformity, and individual parts to define discrete curves and angles.

A team of eight wire artists, some new and some old collaborators, worked with Ralph’s guidance. Each wire frame took around a day to make, made by wire artists who specialise in shaping frames. Weaving over the frames in finer weave by master plasterers took around four days per piece. We condensed 100 days of work into two weeks to make MAYA, the first iteration of Hot Mesh. With the plastering of each module being the work of one artist, the form as a whole takes on the visual symbolism of many people working together for a common goal – and of individuals supporting one another.

Half of the 18 modules were yellow passivated after being zinc electroplated, an industrial process used to protect metal parts from corrosion (thanks Wayne at De Rust It). The gold and silver helps to identify the interwoven pattern of the modules. Ralph connected the modules together using the 3D-printed clips manufactured by Amnova from recycled plastic, and photographed the assembled work in bright sunlight.

Watch this space for further developments!