Info

African Robots is a project to introduce electronics to street wire art, mainly in Southern Africa. A common sight in Southern African cities is that of ‘wire artists’ plying their trade in public places. These are artists who make ingenious use of ordinary steel fencing wire to make three-dimensional objects that they sell at traffic intersections: cars, bicycles, and aeroplanes, as well as animals, fish, birds, and flowers. Making and selling wire art is a means of income, in a country with very low levels of formal employment.

African Robots grew from the desire to collaborate with these artists to create new forms of work. Wire art is ingenious, but it also suffers from a glut of similar items for sale, and new designs stand out. If popular, new designs are copied by other wire artists, spreading through the wire art scene like a virus. Our first project started from a few simple observations – the similarity between these wire objects made by hand, and ‘old school’ computer graphics; and the way motors, mechanics and electronics are sometimes incorporated into wire art, in toy helicopters and remote control cars, push-along toys and radios. Perhaps we could catalyse the production of some African automatons – robotic birds, insects and animals!

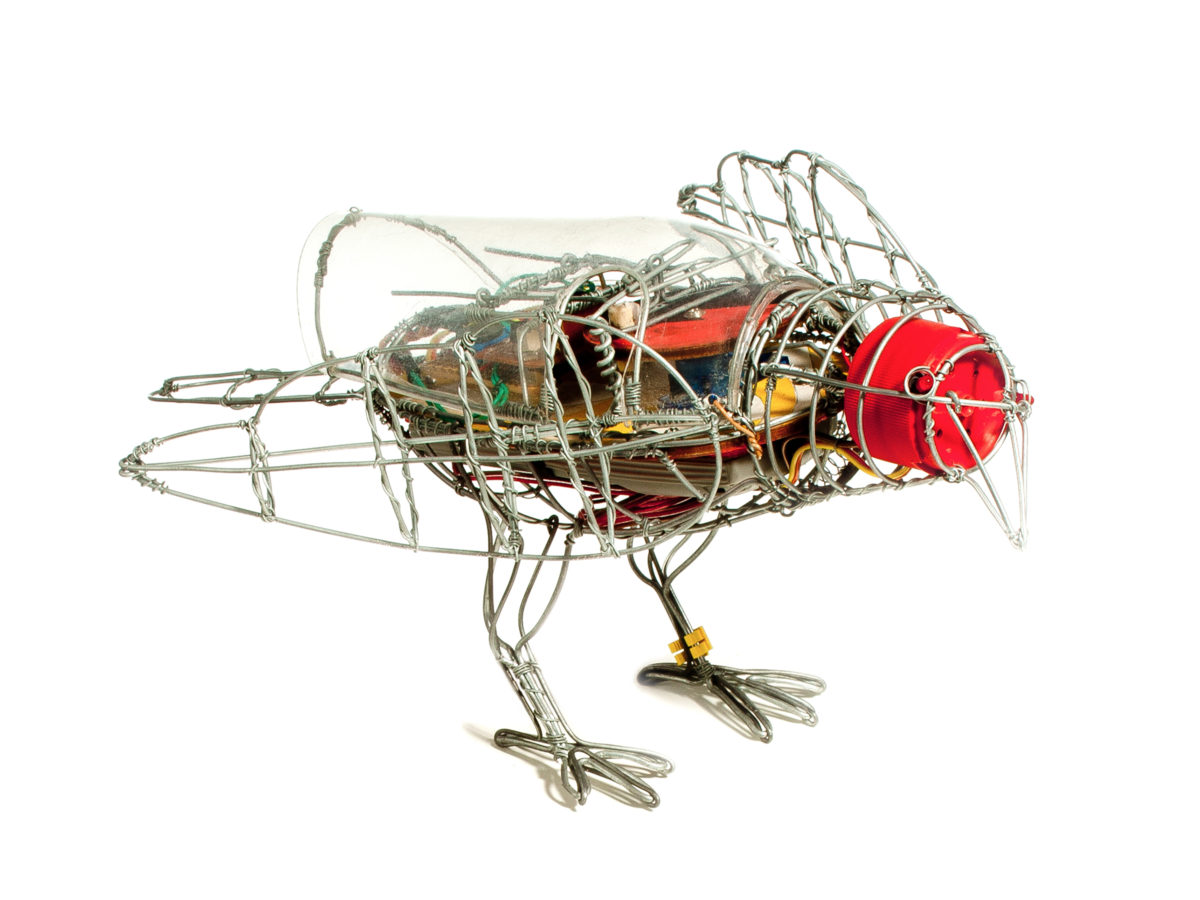

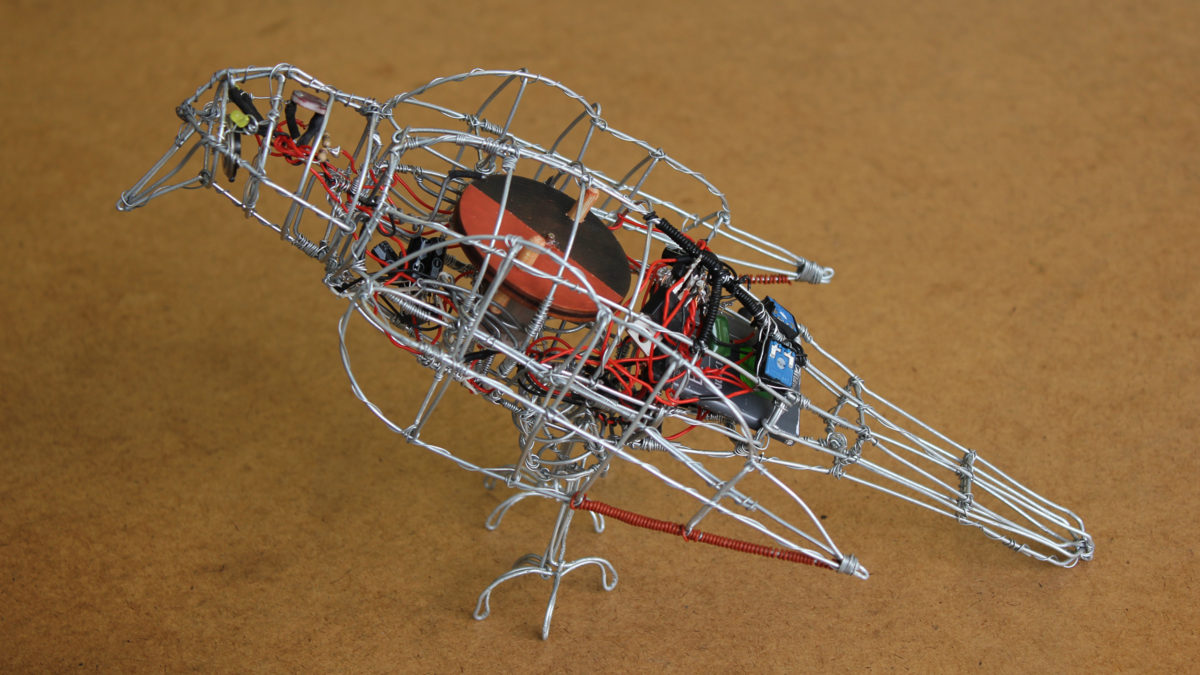

We started exploring this idea on the streets of Cape Town back in 2013 with the creation of our first robot: Starling 1.0! This depicted a nimble local bird, the Red-Winged Starling, in wire art, with innards composed of Nokia cellphone parts and other cheap electronic components, moving wings, glowing eyes, and a light-responsive call. Wire artists share the same urban spaces as informal cellphone repair stalls and shops. We thought: what if these networks could be connected to create simple street-level automatons from wire, waste materials and cellphone parts?

Starling 1.0 was designed in Ralph Borland’s studio with the assistance of a young intern from the Design Interaction programme at Royal College of Art, London, Henrik Nieratschker. We downloaded and modified a simple 3D model of a bird, and printed out profiles to guide its construction in wire by wire artist (and ragga MC) Dube Chipangura who we met selling his wares at a traffic intersection in the suburbs.

We bought an old Nokia cellphone advertised online, and scavenged cheap cellphone shops for parts such as small speakers. We bought cheap electronic components – one of the premises of our project is that basic electronic chips (ICs or integrated circuits) can be as cheap as wire – and built circuits for making sound and controlling motors, based on diagrams shared online. We soldered components directly together to self-consciously create a ‘street level’ feel – we wanted this robot to appear almost as if it could have assembled itself from available materials on the street.

From this simple start, we responded to opportunities to exhibit the Starling – first on the Maker Library stand at Design Indaba in 2014 through our friends Thingking – and to attract attention to the African Robots project to design new forms of interactive electronic wire art. We went on to make two further versions of the Starling, each exploring a different technological and aesthetic approach. Starling 1.1 used a hacked mp3 player with a recording of a real starling on it, while Starling 1.2 used a bird call circuit taken out of a cheap Chinese toy. Each time we made it, we got a chance to explore how to make them more robust and easily repairable – and we met and worked with more wire artists with different styles in the process.

We have learnt a lot from getting to know wire artists in Cape Town, and later in Harare and Maputo (and even in Rio and Sao Paolo!). Wire artists in Southern Africa usually start out making wire car toys as children, and if they’re particularly good at this, other children or their parents buy their cars from them. In later life, they make a living as wire artists. Many wire artists in South Africa are migrants from Zimbabwe. Some wire artists have global reach, sending their goods to other countries. Most are self-employed, but some work for organisations. Some wire artists specialise in production and stay home making art, and others specialise in selling on the streets, and there are different forms of business relationships to manage these.

African Robots works with wire artists in a few ways: we hold workshops in which we introduce wire artists to the concepts of the project, and guide and support them in making new work; and we design new forms for work ourselves, and commission wire artists to work on them. We always pay wire artists for their work, and we use grant funding and commissions to support our programmes (see more about funding). We often work with other collaborators to achieve complex ends, whether that is making custom circuit boards for wire artists to use, or large scale interactive work. We work on an ad-hoc basis as opportunities arise – sometimes for months at a time for larger projects. We have ambitions for an African Robots Workshop, which would create a space in which wire artists could learn, make and sell their wares.

Throughout our work, while the objects we make are important – not to mention delightful! – the relationships and situations we create are just as important. Our intention is to celebrate wire art and bring fresh attention to it as a deeply-rooted vernacular practice that expresses some of the essential artistic urges to observe and represent. It is a resourceful and ingenious medium. We bring wire art and artists into galleries and museums, connect popular culture with fine art, break down barriers between art and craft, and technology with hand-work. We connect communities across social, cultural and economic divides. We’ve situated the work we do in relation to academic fields such as Futures Studies, and Ethnomathematics (wire artists practice topological skills in making a wire describe a 3D form).

In recent years, we have gone from small (and cute) beginnings to large scale, serious works exhibited in museums – such as Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019), a six metre long, 500kg interactive music-making spaceship sculpture exhibited in the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town, which plays on the history of Marcus Garvey’s political activism as celebrated in dub and reggae culture. We used high tech processes such as LiDAR scanning, photogrammetry, 3D modelling and VR sculpting to achieve this. The more resources we have, the more evidence we can produce of the scale of our ambitions, and we are grateful to our funders for helping us to achieve this – such as the National Arts Council of South Africa which funded the Dubship.

Our founder and lead artist Ralph Borland has delivered presentations about the work all over the world, from Cape Town to Harare, Maputo to Dar es Salaam, London to Dublin, Rio to Sao Paolo, and in South Korea, where he applied the African Robots model to work with a local artist there and produce the robot Anthropophagic Octopus. African Robots have been exhibited in London, at the Toronto International Film Festival, at the Vitra Design Museum in Germany, at the Sahara Sparks conference in Tanzania, the Natural History Museum of Ruanda, and in many other places!

If you would like to find out more about us, collaborate, commission work, support us, or just have a chat, please get in touch!